Breaking America’s Law:

On Being Suspect

by Owólabi William Copeland

This essay first appeared in Geez magazine's Spring 2020 issue

“Today I know it’s about all of it: the truth of how violence is handed down as a collective generational thing and the truth of individual agency and accountability for participation in that violence. Healing is the weaving between.”

– Susan Raffo

– Susan Raffo

Do you know how the Detroit Police Department was founded?

Detroit griot Jamon Jordan told us this story as part of his “Two Detroits” tour.

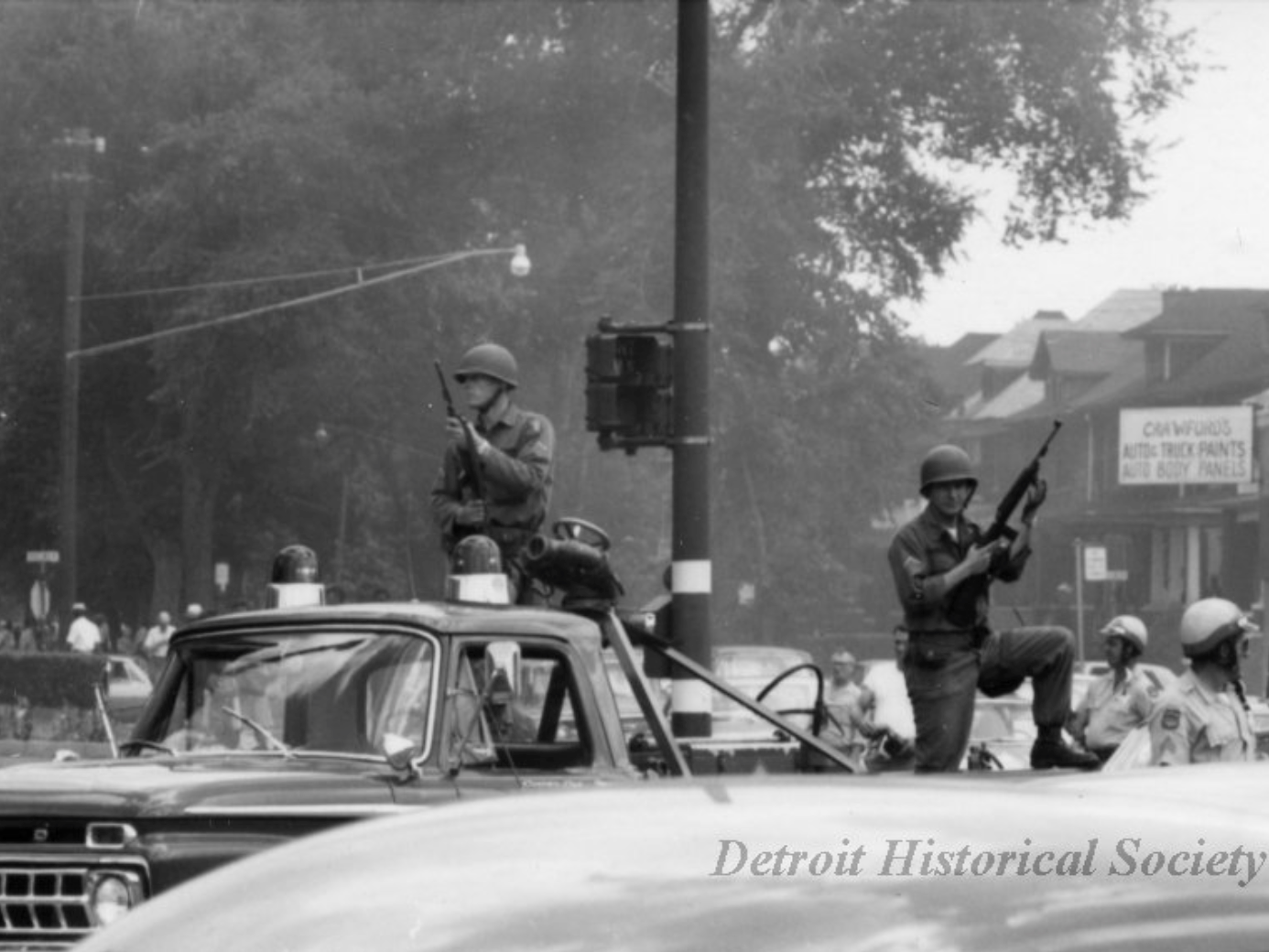

Thornton and Lucie Blackburn escaped from enslavement in Louisville, Kentucky and fled to Detroit, Michigan in 1831 where they lived successfully until slave catchers from Kentucky captured them in 1833. While the couple was held in captivity (prison), the Detroit Afrikan (Black) community organized covertly to safely spring Lucie away to Canada. Then over 400 Afrikans surrounded the jail to liberate Thornton Blackburn.

In the time after Lucie and Thornton’s escape, white people of Detroit rioted, burning down Black-owned buildings and assaulting Afrikans in the street. Soon, African American citizens were obligated to carry a lantern at night to make themselves visible to white citizens. A night watch began to patrol the river and all boats coming to Detroit from Canada were stopped. A 9 p.m. curfew was set and Black people could be forced to show papers at any time to prove their legal status in Detroit.

In response to the Blackburns’ rescue, the city of Detroit formally founded a 16-man patrol so that the forces of the state/slavery/prison system would never be outnumbered or overpowered by the strength of the local Afrikan community. After the Civil War, this patrol became the Detroit Police Department.

What is “breaking the law” when your freedom is not only illegal but systemically inconceivable and unimaginable?

As a Black man, you don’t have to break the law to be punished.

I notice this more and more as a parent. I am teaching my son to not put himself in positions where he can be viewed as a suspect. It’s hard because he has white friends who, already at eight years old, move through society with ease. I don’t want to disturb his ease – this society will try its damndest to do that in the coming years – but I want to teach him to “keep his head on swivel,” as my martial arts teacher would say.

In the last couple years my son has already transformed from “I want to be a police officer,” to “If you mess with the police will they shoot you?” Keep asking the question fearlessly, my son.

It’s very popular to view “the talk” that African American parents give to their children about police from a position of fear. I reject this fearful stance and add nuance to it. We are in an ongoing war. It’s unproductive to fear the enemy, but also unwise to force unnecessary confrontation or to prematurely broadcast one’s intentions.

I think of intergenerational trauma. We learn of punishment not just from the cold impersonal hands of the law, but also from the familial beatings of those who are caring for us. It is said that it is better to be whupped in the home to learn discipline and boundaries from those who love you than be caught on the street where the enforcers don’t have your best interest at heart.

And it must have been successful because the same tactics honed to avoid paternal punishment are the ones that I use on the streets of my enemy. I have mastered the cloak of invisibility and silence in order to re-emerge as my recharged self, glorious in another, safer space and time.

I see myself in white spaces. I do not move with ease. I have the “double consciousness” W.E.B. DuBois speaks of, viewing myself both subjectively as an embodied spirit and also “psychotically” from the perspective of this sick racialized society that mainly sees a “Black body”– an other – a suspect – a perpetrator – a threat.

And I manoeuvre to minimize those readings.

I do not teach my son to be afraid of police, although they do kill Afrikans for their perception of breaking the law. I say “perception” because the corpse cannot stand trial, so the Black person dies a perpetual suspect in this country. In these incidents, it’s never established if the person who was killed broke any laws. It’s very legal for an Afrikan to be “justifiably” killed as a suspect or threat and never make it to trial.

In the United States of America, the law and the mob are damn near congruent. I don’t respect the law, but I recognize the power of the American mob to punish those they see as suspect. White people are too genteel to string up suspects themselves like they used to 50-100 years ago, so they get the police to do their communities’ lynching.

I follow natural law, but as a colonized person our culture has been forced to assimilate to sickness for a long, long time. Within my daily rituals of Orisha, we say invocations for protection: to avoid trouble, to avoid sickness, to avoid poverty. One of the last ones I have been taught is to avoid police and thugs.

I learned over many years the distinction of appearance and essence. They project onto me the appearance of a wrongdoer so I project back the appearance of staying within the lines.

Well, it is true that I spend 20 hours per day thinking of how to overturn their depraved system. Maybe they are tactically right to view me suspiciously?!

Eneke the bird was asked why he was always on the wing and he replied: ‘Men have learned to shoot without missing their mark so I have learned to fly without perching on a twig.’

– Proverb as told by Chinua Achebe

– Proverb as told by Chinua Achebe